God Meets Us in Grief: Finding Hope in Ezekiel

It was in the middle of the week when I learned that Renee died. I remember how I felt as I put down the phone: the tightness in my chest, my lungs struggling to fill. I remember thinking that this must have been similar to how she felt as she struggled with pneumonia in those final days. I remembered all the small things at once. When we talked about the new project she was working on. When we laughed a little too loudly eating Mongolian BBQ in a small local restaurant. When she carried an enormous blue and orange stuffed giraffe for my daughter that took up almost her entire toddler bed. When I got off that call, I was wrecked with shock, with loss, with grief. I cried out to God asking why he had to let her die.

Enjoying this article? Read more from The Biblical Mind.

It has been over a decade now since Renee’s death, but I still wince inwardly when I think of her, as if feeling an old injury that never completely healed. Her death still comes to me unexpectedly, and I’m back in my grief, lamenting her loss. Her death along with the death of others launched me on a journey to understand how God meets us in our grief, our loss, and our suffering and what Scripture tells us about this. It was during this journey that I “met” the biblical prophet Ezekiel and found a companion to walk with me down this difficult road.

The Prophet Ezekiel: A Friend for the Painful Journey

Ezekiel was a prophet during one of the darkest periods of Israel’s history: the Babylonian exile. After the reigns of King David and his son King Solomon, Solomon’s son Rehoboam caused the once united monarchy to divide into the Northern kingdom of Israel and the Southern kingdom of Judah. Though both kingdoms lasted for a while, in the 700s B.C.E. the large neighboring empire of the Assyrians invaded and destroyed the Northern kingdom of Israel. This left the small Southern kingdom of Judah vulnerable. In the 500s B.C.E., the new large empire, Babylon, invaded and destroyed the temple in Jerusalem, killing many in brutal warfare, and taking the leaders of the area into captivity.

This exile of these leaders in Babylon we call “the Babylonian exile” or put more simply “the exile.” Psalm 137 represents the pain of Babylonian exile as the Israelite people sat by the rivers of Babylon and wept when they remembered their home so far away, left in ruins.

Ezekiel bears witness to this trauma. Sometimes people struggle with reading Ezekiel, especially its beginning chapters. Unlike the book of Isaiah, which alternates between judgment and hope, the first 33 chapters of Ezekiel feel mostly like a deep dive into loss and violence. Ezekiel’s actions, such as cutting off his hair, laying on his side for months at a time, and eating food cooked over dung, can seem outrageous and irrational. But this is intentional. To help the people find God amid the mess of the exile, God asks Ezekiel to act out key scenes from Jerusalem’s destruction. The marks on Ezekiel’s body, the weird things he does, and the food he eats all tell the story of the Israelites’ trauma and loss.1Refael Furman, “Trauma and Post-Trauma in the Book of Ezekiel” Old Testament Essays, 33(1) (2020), 32–59. By telling this story, the Israelites can work through their trauma. They can face their horror and their shock and, in this way, start the process of healing.

After nearly 33 chapters that show and tell these experiences of trauma, Ezekiel 34 marks a turning point. Ez 34 begins with judgment, but then turns to hope. Ez 34 starts with God’s warnings about the judgment that will fall on the false shepherds, the wicked leaders of Israel, who did not care for the Israelite people properly and caused the exile. But then in Ez 34, a figure of hope emerges: a true shepherd who will care for God’s people. This shepherd is God himself. God promises that the upside-down world, which the Israelites have experienced in the exile, will be turned right-side up again. Ezekiel portrays this promise in two ways: through the metaphor of God as Israel’s shepherd, and through the structure of Ez 34 itself.

God as Shepherd as a Metaphor of Hope in an Upside-Down World

While Ezekiel’s metaphors in Ez 1–33 tend to picture the violence and loss experienced in exile, Ez 34 shifts to a picture of restoration, hope, and peace through the metaphor of God as Shepherd. In the ancient world, the term “shepherd” was often used not only of literal shepherds who take care of sheep, but of leaders and kings. For example, there are images and statues of ancient Egyptian pharaohs with a shepherd’s staff in their hands, being referred to has a “shepherd” of their people.

In v. 10, we see God’s choice to remove his sheep (a.k.a. his people) from the wicked shepherds/leaders. After removing them, God takes over the role as their shepherd in vv. 11 as he searches for his lost sheep. He officially proclaims himself their shepherd in v. 12. As their shepherd, God offers his people the hope that they will be restored and the most vulnerable and hurt among them will be cared for. God knows what has happened to them. God cares for them. God will heal them.

But this hope also comes as God judges not only the leaders who hurt the people and allowed the exile to happen, but God also judges the strong and powerful among the people who have committed injustice against their own people––pictured as “fat sheep” who trampled their fellow sheep (vv. 17–22). Hope comes not only because God promises to restore and heal, but also because God promises to bring justice in situations of injustice within the community itself. To restore order to his people, God needs to root out not only the outside forces that have hurt them, but also the ones within who have hurt them as well.

The passage culminates with a final hopeful picture of a shepherd like David who will tend the sheep under God’s direction (vv. 23–24) and God’s creation of a “covenant of peace” giving safety and flourishing to the land and the people (vv. 25–30).

Besides seeing the value of Ez 34 in its time, we may also hear the reverberations of Ezekiel 34 in Jesus’s description of himself as “the Good Shepherd” in John 10. John 10 references Ezekiel 34 directly in several places to connect Jesus’ role as the “good shepherd” to his sheep with God’s role as caring and restorative shepherd to his people in Ez 34. Like the picture of God as shepherd in Ez 34, Jesus as good shepherd in John 10 offers hope to the people of his time.2Brian Neil Peterson, John’s Use of Ezekiel: Understanding the Unique Perspective of the Fourth Gospel (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015) 129–164.

The Structure of Ezekiel 34: Turning the World Right-Side Up

Not only does this metaphor of God as Shepherd provide a picture of hope for God’s people, but the structure of Ezekiel 34 itself also echoes this hope. Ezekiel 34 has a structure that we sometimes call a “chiasm.” A chiasm works with a structure of ABCCBA. As simple example is Dr. Suess’s poem, ”My Hat is Old” from One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish (See figure 1 above). The first line that starts “My hat is old.” is A, “I have a bird” is B, and “My shoe is off” is C. These phrases are repeated in upside down order as Dr. Suess’s creature turns himself upside down. (See Figure 1 below.)

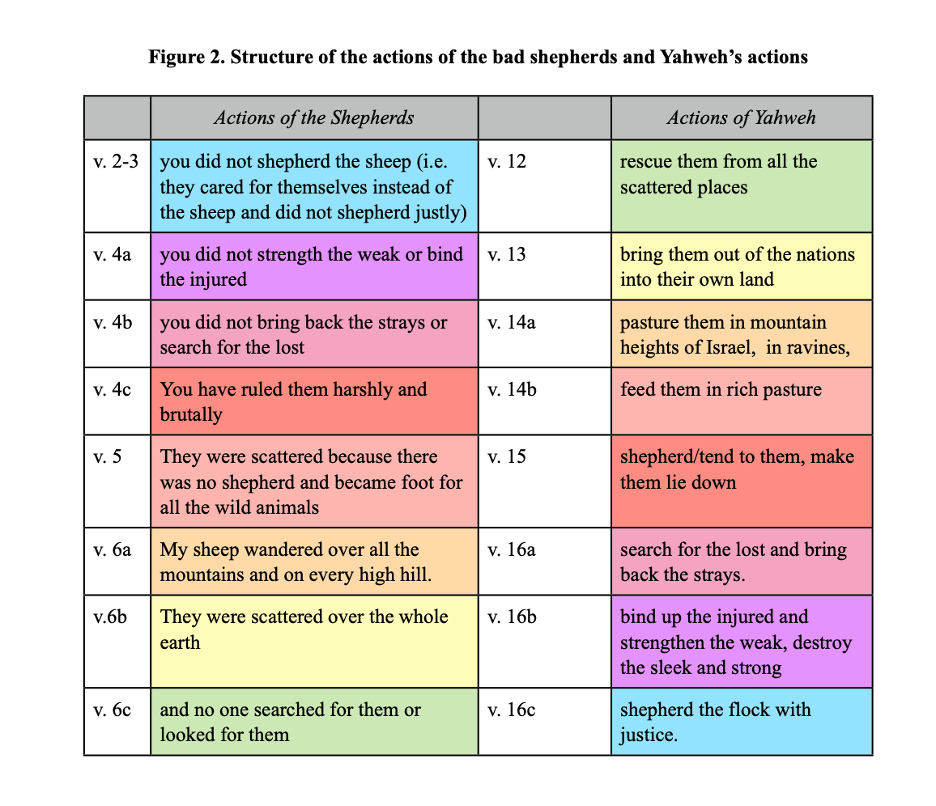

Though a bit less obvious, Ezekiel has a chiastic structure similar to that of the Dr. Suess poem. Verses 2–3 speak of shepherds who do not care for their sheep. They do not strengthen the weak or bind the injured. They do not bring back the strays or the lost. These verses are paired with their complete opposite given in reverse order in v. 16 where God searches for the lost and brings back the strays. God binds up the injured and strengthens the weak (and additionally destroys the sleek and the strong). God cares for the sheep by shepherding them with justice. It is possible to chart this chiasm from vv. 2–6 and vv. 12–16. (See Figure 2 below).

When the Babylonians came in, they turned the Israelite’s world upside down and Israelite’s leaders (their shepherds) let this happen. Ezekiel 34 uses this reversed structure to show how God as Israel’s Shepherd will turn the world right-side up again. God will turn the chaotic world of trauma and violence into the right order of peace (Ez 34:25).

Ezekiel 34 for Today

Ezekiel continues to offer a way through trauma and a way towards hope for us today. In the first 33 chapters of Ezekiel, Ezekiel offers a vision of the real pain, loss, and violence that many will find resonant with their own experience. While most of us have not been through the destruction of war and being exiled like Ezekiel had, we have all experienced loss, grief, and suffering of different kinds. We like Ezekiel have asked where God is in the messiness and darkness of life.

Ez 34, and its New Testament counterpart in John 10, offer a picture of how God will show up in the middle of our mess and “shepherd” us back, binding up our wounded places, strengthening us in our weakness, and restoring justice.

Though Ezekiel does not fully remove the pain from my loss of Renee and will not remove our personal losses, Ezekiel provides a pathway for us to understand how much God wants to meet us in our pain and grief and restore us. God wants to turn the world right-side up again.

End Notes

1. Refael Furman, “Trauma and Post-Trauma in the Book of Ezekiel” Old Testament Essays, 33(1) (2020), 32–59.

2. Brian Neil Peterson, John’s Use of Ezekiel: Understanding the Unique Perspective of the Fourth Gospel (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015) 129–164.

Subscribe now to receive periodic updates from the CHT.