The Sabbath as a Key to Understanding Biblical Law, Part 1

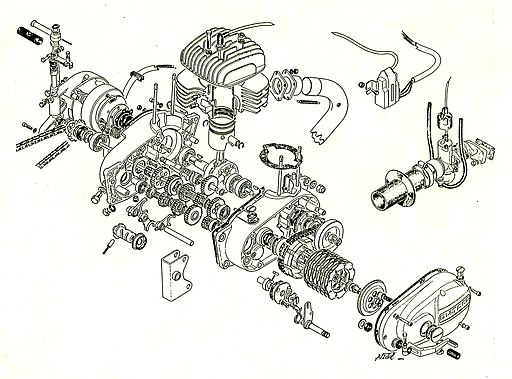

As a child, I enjoyed books with “exploded” views of great machines, within which all the component parts of some vast mechanism were visible and their interrelations manifest. Looking at such diagrams, one could imagine all the exploded elements being compressed back into their proper places within the mechanism, seeing that object in a very new light and with a new understanding.

Throughout Scripture, in feasts, edifices, history, case law, legal exposition, and prophecy, we are given an “exploded view” of the Sabbath. Having reflected upon it, we can return to the fourth of the Ten Commandments—remember the Sabbath day—and see it anew, as if for the first time.

The Sabbath is a condensed expression of the entire meaning of the Exodus. It connects the Exodus back to the creation, the intent of the Exodus being related to the completion of creation and the enjoyment of God’s rest. It perpetuates the force and meaning of the Exodus in Israel’s continuing life, drawing their eyes back to that first deliverance and forward to its fuller realization that is still awaited.

Enjoying this article? Read more from The Biblical Mind.

As its central sign, the Sabbath can be understood as a symbolic concentration of the meaning of the covenant formed with Israel at Sinai. Closer attention to the way the principle of the Sabbath gets refracted and unfolded will illuminate both its content and intent, aiding our understanding of biblical law more broadly and our observance of Sabbath more particularly.

A Note on Understanding the Law

Our understanding of any matter is best demonstrated in the ability both to express it in the simplest and most condensed terms and to expound it in its fullest and most elaborate form (see Venkatesh Rao’s suggested definition of the concept of “literacy” in this post). Albert Einstein once famously remarked that “If you can’t explain it to a six-year-old, you don’t understand it yourself”: it is only possible to express complex concepts simply when you have fully digested them yourself. The other side of true understanding is the capacity to expound: to take the pure light of a particular truth and, through the prism of one’s insight, to refract it into a rich spectrum of further truths that arise from it.

Perhaps this is nowhere more evident than in the biblical law. Throughout Scripture we see condensations and expositions of the law and persons’ understanding of the law manifested in their facility in moving between the two. At times, wisdom is demonstrated in the ability to comprehend the entire law in condensed principles. Most famously, when asked which of the commandments was the greatest, Jesus summed up the entire law in two great commandments: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind” and “you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Matthew 22:36–40). At other times wisdom is demonstrated in the perceptive and creative application of more abstract principles to a variety of specific circumstances.

The law itself has a structure that invites and encourages sustained meditation upon and familiarity with the relationship between condensed principles and expounded applications, between specific commandments and the larger system, and between positive practice and negative proscriptions. Perhaps the most significant example of this is found in the book of Deuteronomy, where the Ten Words of the covenant (commonly referred to as the “Ten Commandments”) in chapter 5 are followed by twenty-one chapters of exposition (chapters 6 to 26), within which various dimensions of each of the Words’ application are expounded in succession.1The enumeration of the “Ten Words” or “Ten Commandments” comes from Exodus 34:28, Deuteronomy 4:13, and 10:4. Without fleshing it out more extensively here, I believe that the order is broadly as follows: Deuteronomy 6-11—The first commandment; 12-13—The second; 14:1-21—The third; 14:22—16:17—The fourth; 16:18—18:22—The fifth; 19:1—22:8—The sixth; 22:9—23:14—The seventh; 23:15—24:7—The eighth; 24:8—25:3—The ninth; 25:4—26:15—The tenth.

The hearer who recognizes this relationship between condensed principle and expounded application is provoked to reflect upon the logic of the relationship, and upon further potential applications, as the exposition of the principles, though exemplary, is not comprehensive. There are many situations that they don’t address, yet the person whose understanding has been formed by meditating upon the condensation-exposition relationship will be prepared to consider novel scenarios.

The Sabbath in the Ten Words

The commandment concerning the Sabbath provides a very good example of how our understanding can be enriched through this kind of meditation on the law. In its original form in Exodus 20:8–11, it is given as follows:

Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor, and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter, your male servant, or your female servant, or your livestock, or the sojourner who is within your gates. For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy.

Traditionally, many theologians have spoken in terms of two “tables” of the law. These two tables have been variously ordered, often according to the overarching principles of love for God (the first table) and love for neighbor (the second table).

Reading the Ten Words, we might notice contrasts between the first five commandments and the second five.2I follow a Reformed Protestant ordering of the Ten Words but cannot argue for it in detail here. Merely looking at them printed on the page, we might observe the terse character of commandments six to ten in contrast to commandments one to five. The cause of this contrast becomes more apparent as we recognize that each of the first five commandments has an attached rationale, warning, or promise, whereas the latter five stand alone. A further distinction is the presence of the name of the Lord in the first five, in contrast to its absence in the latter five.

With respect to their content, the first five commandments could be considered as dealing with “vertical” relations with parties in authority over us, chiefly with God, but also with parents. The latter five commandments are “horizontal” commandments, addressing our relations with our neighbors.

All but two of the commandments—the Sabbath commandment and the commandment to honor father and mother—are framed in a negative form (typically “thou shalt not . . .”). However, when we see the intent of the commandments summed up, they are overwhelmingly comprehended in positive injunctions: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind” and “you shall love your neighbor as yourself. (Matt. 22:37–39; cf. Deuteronomy 6:5; Leviticus 19:18). The implication of this is made explicit in the teaching of the New Testament: law is fulfilled in the positive pursuit of love, not chiefly in the avoidance of proscribed acts (Romans 13:8–10; Galatians 5:14; James 2:8).

The presence, then, of positive injunctions at the heart of the Ten Words might be noteworthy. If one removes the “thou shalt nots,” with what is one left? The setting apart of one day in seven to memorialize the great deeds of the Lord, to enjoy rest oneself, and to give rest to others, and peace and honor between husband and wife (father and mother) and successive generations.

Sabbath, Covenant, and Tabernacle

Expanding the scope of our attention slightly further, it becomes apparent that the Sabbath is not merely one of the Ten Words, but instead occupies a central place in the covenant. In Exodus 31:12–17, the institution of the Sabbath is presented as the great sign of the covenant, functioning in a manner akin to circumcision in the Abrahamic covenant (cf. Genesis 17:9–14):

And the Lord said to Moses, “You are to speak to the people of Israel and say, ‘Above all you shall keep my Sabbaths, for this is a sign between me and you throughout your generations, that you may know that I, the Lord, sanctify you. You shall keep the Sabbath, because it is holy for you. Everyone who profanes it shall be put to death. Whoever does any work on it, that soul shall be cut off from among his people. Six days shall work be done, but the seventh day is a Sabbath of solemn rest, holy to the Lord. Whoever does any work on the Sabbath day shall be put to death. Therefore the people of Israel shall keep the Sabbath, observing the Sabbath throughout their generations, as a covenant forever. It is a sign forever between me and the people of Israel that in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day he rested and was refreshed.’”

As a central covenant sign, the Sabbath was holy, but also a sign that the people to whom it had been given were holy. Within its observance, Israel would both recognize the Lord as their God, and also themselves as his special possession. The Lord was giving them his rest because they were his people.

The Sabbath commandment in Exodus 31 appears in the context of the instructions for building the tabernacle. Looking at the material concerning the building of the tabernacle more broadly, this connection might not be accidental. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the instructions for the tabernacle are given in two successive cycles of seven phases, patterned after the days of creation. Within this framework, the completed tabernacle is associated with the Sabbath, being presented as a sort of sabbatical place. This association can be strengthened by attention to the allusions back to the creation account at the end of Exodus, as Moses finishes the work constructing the tabernacle and the tabernacle is consecrated, much as the Sabbath day was at the end of the original creation week. The tabernacle is a place of the Lord’s rest amid his chosen people, with the intent that his people will enter his rest themselves, as they meet with him in his palace tent, and that they will extend it to their neighbors and those within their own houses.

We might consider the tabernacle as extending the principle of rest from times to places. However, perhaps it would be better to recognize the way that, although it is a physical object and place, much like the sun in the heavens, the tabernacle functions temporally, governing and marking the times of Israel. The daily sacrifices, one lamb at morning and one at twilight, set the times of Israel’s days and nights (Exodus 29:38–42). The tabernacle is also the site of festal gathering, where Israel presents itself before the Lord at three appointed times every year. The tabernacle is a building that structures Israel’s times, only properly understood when we consider the sacrificial and festal itineraries to which it gives order, place, and focus.

As the rationale for the Sabbath in Exodus 20 is associated with God’s own rest in creation, we might regard the purpose of the Sabbath as both memorializing God’s rest and bringing Israel into enjoyment of it. The tabernacle—the Lord’s Sabbath tent—is, as it were, the seed of a new restored creation and, as Israel’s life is ordered in terms of it, they will participate in something of God’s creation rest.

Sabbath and Liberty

In the chapters following the giving of the Ten Words in Exodus 20, we find several instances of the Sabbath principle being unfolded as an ethic for the treatment of vulnerable community members. The body of case law in chapters 21–23 opens with an application of a Sabbath principle to the institution of slavery. Exodus 21:2 says, “When you buy a Hebrew slave, he shall serve six years, and in the seventh he shall go out free, for nothing.”

The Lord set Israel free from its slavery and gave them his Sabbath rest. In such case laws, Israel is called to treat their slaves in a similar manner. The Mosaic law reorders slavery toward liberation. The liberation enjoyed collectively by the nation must be extended to all its members. And, in the sabbatical form given to these laws of emancipation, Israel must recognize the foundation of its society in an act of the Lord’s liberating grace and its duty to live in terms of that grace, communicating it to others.

There are some minor variations between the Sabbath commandment as given in Exodus 20 and the commandment recorded in Deuteronomy 5. The most notable of the differences is found in the rationale in verse 15. The Sabbath commandment was grounded in creation in Exodus; in Deuteronomy it is grounded in Israel’s redemption from Egypt:

You shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Therefore the Lord your God commanded you to keep the Sabbath day.

The celebration of a weekly rest is a repeated memorial of the Lord’s gift of rest to Israel. In the laws of slavery and elsewhere there is a refraction of the Sabbath command into broader principles of liberation in Israel’s society. To keep the Sabbath is not merely to rest—and to give rest—one day in seven, but to uphold a society in which no one is subject to the burdensome and unceasing labor that characterized Israel’s life in Egypt. The Sabbath day was a repeated reminder of the Lord’s intent that all in Israel—from the richest to the poorest, native and stranger—should know him as their liberating God.

Indeed, this principle of liberty and release extended to the wider creation. One year in seven, the land was to lie fallow (Exodus 23:10–11) and, on the seventh day, even the ox and the donkey were to be given rest (Exodus 23:12).

The Sabbath and the Poor

Another vulnerable group meant to benefit from the Sabbath principle was Israel’s poor. The material of Deuteronomy 14:22–16:17, which expounds the Sabbath law, opens with a discussion of the tithe, moving from the annual tithes to the tithe of the third year. A few things are worth noting about the tithes’ purposes: The tithes connected the people to the sanctuary, since they had to present them at the Lord’s Sabbath tent at the appointed time. The tithes also served a charitable and hospitable end: the Levites, the fatherless, the widows, the sojourners, and the poor were singled out to share in the enjoyment of the tithe feasts.

It is striking to see that the practices of tithing first treated in 14:22–29 reappear at the conclusion of this larger section expositing the commandments in chapter 26, implicitly classed under the tenth commandment, which forbids coveting. There Israelites are charged to recall and declare the great deeds of the Lord in bringing them into the land, to present the Lord with its fruits, to celebrate before him, to share with those in need, and to give the commanded portion to the Levite, widow, fatherless, and stranger.

Tithing—a key form of the logic of Sabbath—is associated with celebration and declaration of and thanksgiving for God’s goodness, with joyful assembly, generosity to others, and contentment in his bounty. It is found under the tenth commandment in Deuteronomy 26 because this is what the alternative to coveting one’s neighbor’s possessions looks like: delighting in the blessings that you have received, practicing thanksgiving, and generously giving to others. This is what it looks like for the tenth commandment to be fulfilled.

In chapter 15, the exploration of the Sabbath principle moves from the tithe to the Sabbath year and the release of debts and slaves. In the context of the laws concerning the Sabbath year, there is instruction given concerning treatment of the poor more generally. Verse 11 says, “For there will never cease to be poor in the land. Therefore I command you, ‘You shall open wide your hand to your brother, to the needy and to the poor, in your land.'”

Central to the purpose of the Sabbath commandment seems to be a concern for the poor, the enslaved, the needy, and the dependent.

From chapter 15’s discussion of debt, poverty, and slavery, chapter 16 transitions to the annual pilgrimage feasts of Unleavened Bread, Weeks, and Booths. These feasts integrate several purposes of the Sabbath. They connect the Lord’s rest with his people’s, by releasing the people from their labors and gathering them to his Sabbath tent for celebration. They memorialize the great deeds and deliverances of the Lord that the feasts commemorate. Associated with times of harvest, they relate the gifts of the land back to their true Giver. Finally, they ensure that all people can enjoy God’s gifts and rest.

End Notes

1. The enumeration of the “Ten Words” or “Ten Commandments” comes from Exodus 34:28, Deuteronomy 4:13, and 10:4. Without fleshing it out more extensively here, I believe that the order is broadly as follows: Deuteronomy 6-11—The first commandment; 12-13—The second; 14:1-21—The third; 14:22—16:17—The fourth; 16:18—18:22—The fifth; 19:1—22:8—The sixth; 22:9—23:14—The seventh; 23:15—24:7—The eighth; 24:8—25:3—The ninth; 25:4—26:15—The tenth.

2. I follow a Reformed Protestant ordering of the Ten Words but cannot argue for it in detail here.

Image created by Rubner Durais

Subscribe now to receive periodic updates from the CHT.