Does It Matter if You Don’t Feel Close to God?

Have you ever said a word over and over until it sounded bizarre to your ears, as if you’re hearing the word for the first time as a non-native speaker? “Sweetener, sweetener, swee-tener, sweet-en-er, sweeten-er, sweetener.” The familiar becomes suddenly strange. Words are so near to our mouth that they feel as if they’ve always been there in the same shape and formation.

Enjoying this article? Read more from The Biblical Mind.

Often, when I’ve been away from home for a while, my mind drifts to my wife and children. And as I think about how much I miss and enjoy them, I play little movies of them in my head over and over. Like “sweetener,” they become fleetingly unfamiliar to me. Sometimes as I think of my wife, it begins to seem strange, if only for a moment, that we’re even married to each other. What is the nature of the bond we share? It feels weird to be connected to a person who is so accessible to me and yet another creature entirely.

Maybe you’ve never felt this alienation from words or family members, but you probably have felt distant from God. Maybe everyone in your worship service except you seems to be in direct communion with the Almighty. Or, maybe a lingering depressive cloud has muffled your sense of God’s care for you.

Why do we often not feel close to God? Why does God often seem to be like a word we keep repeating until estrangement? Conversely, why do so many of us feel close to God when encountering the majesty of nature, or in a prayerful worship service?

In Scripture, closeness to God is essentially an activity rather than a feeling. A community maintains closeness to God by living under his guidance.

Being Close to God Isn’t a Feeling

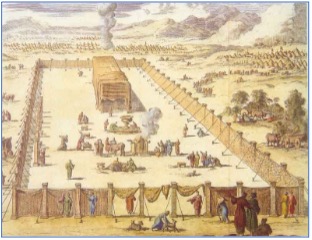

Ancient Israel might not have had this struggle to sense God’s presence—at least not in the same way that we feel it. For them God had a specific address, a locale to which they could point if someone asked them, “Where is God right now?” God’s presence was to be found seated upon the Ark of the Covenant (also known as the mercy seat) and in the Holy of Holies of the mobile Tabernacle (and later in the permanent temple at Jerusalem). They could point not only to a tent, but also to a specific back room in the tent and say, “There is God!”

Israel was instructed on how to be in God’s presence, but God’s presence creates the conditions for taking his instruction seriously. Presence and instruction go hand in hand.

The common Hebrew term for a sacrificial offering is korban, which literally means “nearness thing.” Israelites got close to God, physically, and they had to bring a nearness-allowing offering to do so (Deut 16:16: “They shall not appear before me empty-handed.”). Israel was instructed on how to be in God’s presence, but God’s presence creates the conditions for taking his instruction seriously. Presence and instruction go hand in hand.

Deuteronomy presents God’s loving instruction—the Torah—as the thing that makes God close to Israel. It’s a new idea for many of us: God’s teaching itself forms part of what it means for Israel to be close to God:

Surely, this commandment that I am commanding you today is not too hard for you, nor is it too far away. It is not in heaven, that you should say, ‘Who will go up to heaven for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?’ Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, ‘Who will cross to the other side of the sea for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?’ No, the word is very near to you; it is in your mouth and in your heart for you to observe. (Deut 30:11–14)

So Israel can be close to God because they have been instructed in how to embody the justice/righteousness of the Torah: caring for the vulnerable, equal application of law for the foreigner, maintaining truth in testimony, avoiding the fracturing of families, eschewing bribes, self-reporting on a host of cleanliness and holiness statutes, and so on. This direct instruction from God makes Israel remarkably different from the surrounding ancient Near Eastern cultures. Other ANE gods don’t speak to humans, much less care about them enough to instruct them and bind themselves to mere humans in covenants—which create the necessary conditions for repentance that keeps God’s presence near to them.

Notice that keeping God’s presence near to Israel is a team sport; it’s more like soccer than tennis. And Israelites are not only concerned with getting close to God, but also with maintaining God’s nearness. It’s the same in the New Testament—the nearness of God’s instruction, team justice, and maintaining God’s closeness—with some strategic changes.

God’s Address Change

What changes in the New Testament? Jesus is identified as Isaiah’s imannu-el, literally, the “with-us God.” In the Gospels, Jesus is not just near to us in his incarnation as a man on earth. If that were the case, Jesus would need to remain on earth for us to be close to God. But he didn’t stay. He left. And when Jesus left, he gave a promise to be near by sending the Holy Spirit. God’s presence also corresponds to his instruction. Jesus’ presence in Galilee is explicitly for the sake of instructing his disciples. The Holy Spirit’s presence, whom Jesus calls the “counselor/advocate” (paraclete), “will guide you into all truth” (John 16:13).

There’s not much new in the New Testament. However, there is one thing that a first-century Israelite would have trouble getting their head around: God’s location changes from the temple to the bodies of believers.

There’s not much new in the New Testament. It flows readily from the Hebrew Scriptures. However, there is one thing that a first-century Israelite would have trouble getting their head around: God’s location changes from the temple to the bodies of Jewish believers (and later Gentile believers).

Close to God by the Blood of Christ

Picturing Jesus now resurrected, interceding for us, and enthroned, both Hebrews and James will both insist that we can “draw near” to God confidently (Heb 4:16; 7:19, 25; 10:1). What permits us to get this close to God? Jesus’ work on our behalf and our trust in having received cleansing from our sin. “Let us draw near with a true heart in full assurance of faith, with our hearts sprinkled clean from an evil conscience and our bodies washed with pure water” (Heb 10:22).

James describes something very similar in his epistle: “Draw near to God, and he will draw near to you. Cleanse your hands, you sinners, and purify your hearts, you double-minded.” The Levitical notion of uncleanness represents the normalcy of our sin that keeps us from drawing near to God. It’s both a recognition that we can trust God and the obvious response that carries obligations for how we live.

Hebrews highlights the fact that we have become a priesthood, those who can now “draw near” to Jesus’ throne because of his work on our behalf. James reminds us that we cannot merely receive such a designation without an appropriate response to it.

But both writers also know that these are metaphors about closeness. We cannot physically get closer to God because God is already and always with us. We are as close as possible, and so the question becomes: Why don’t we feel close to someone who is always with us?

Experiencing Nearness to the ‘With-Us God’

Paul compares Jesus’ teaching to God’s drawing us near, and he uses the nearness-through-instruction language of Deuteronomy 30 (above) to do it: “But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. . . . And he came and preached peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near.” (Ephesians 2:13, 17). Now read what he goes on to say:

For through him both of us have access in one Spirit to the Father. So then you are no longer strangers and aliens, but you are citizens with the saints and also members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the cornerstone. In him the whole structure is joined together and grows into a holy temple in the Lord; in whom you also are built together spiritually into a dwelling-place for God. (Eph 2:18–22)

Although the Holy Spirit comes to be with individuals, it’s the community of God that is his natural habitat. In Paul’s customary framing, because this is true, then we should respond accordingly. As God’s instruction came to Israel and God’s authority rested on his throne in the Tabernacle, so God’s guiding presence persists with us through the Holy Spirit. But to say that “I want to feel close to God” is somehow separate from “I want to embody God’s instruction” seems out of whack with the whole reason for God’s presence as the Holy Spirit.

To say that “I want to feel close to God” is somehow separate from “I want to embody God’s instruction” seems out of whack with the whole reason for God’s presence as the Holy Spirit.

It’s not only in majestic spaces in nature where Christians often report feeling close to God, but also in large gatherings of Christians—God’s new habitat—focused on each other and on God. What is it about these scenes that make us feel close to God? It’s the community we gather with more than the supposed feeling of God’s presence, whatever that might mean to us, that provides the greatest cumulative sense of the reality of his nearness.

Paul also addressed this universal desire of humans to feel close to God in his speech at Athens. Laying it out for the thinkers of the age, Paul tells them “that they should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward him and find him. Yet he is actually not far from each one of us, for ‘in him we live and move and have our being.'”

For Paul, there are many evidences of God’s closeness, just like there are many things that make me feel close to my wife. These include our shared experiences, feelings that wax and wane, smells, inside jokes, and all the things beyond my feeling close to her at any given time.

Certainly, God sees his own acts of faithfulness to Israel and its extension into the church as evidence of his proximity to us. This also explains why God gets so irritated by Israel’s turn to Baalism: “[Israel] did not know that it was I who gave her the grain, the wine, and the oil, and who lavished upon her silver and gold that they used for Baal” (Hos 2:8). Though Israelites might not have lived close to the Temple at Jerusalem, God’s anger at being a jilted spouse derives from his faithfulness to provide.

Most of the hours of my day are spent at work with people who aren’t my wife. But the dozens of daily acts of faithfulness between us make us feel close: from greeting her with embrace in the evenings to celebrating her wisdom to my students.

He Was There the Whole Time

Ancient Israel could point to a spot on the map and declare, “There is God, and this is how close we are to Him.” God was present; they just had to maintain holiness and justice to approach God’s presence. The blending of God’s instruction with his presence was new in this ancient world. No other gods were present to their people and actively engaging them.

Christians are reminded in just about every writing from an apostle that God is with us in his instruction to us through the ages and by his Holy Spirit. “Do this in remembrance of me” and “as often as you did this” are uttered together with “and I will be with you to the end of the age.” Living out God’s instructions as a community, re-contextualized through Jesus, is a way to experience the presence of God. Even though our guided communities are responding to God’s nearness, both his instruction and our responsiveness to it are part of his presence with us. He was there the whole time.

Hence, it makes sense that it might feel easier to focus on God’s presence when we’re in nature or immersed in something otherwise grand or majestic—in those moments, we’ve removed the distractions. Similarly, gathering as God’s children in worship can quiet our noisy thoughts and lives, and we might feel closer to the God who was always there.

When we say, “I don’t feel very close to God,” we say it rightly. We don’t feel it; its reality is independent of our feelings, which can vary from moment to moment. The earliest church, consisting only of Israelites who experienced God’s presence at a specific address in Jerusalem, reminds us that God is present in us. We no longer must maintain community-wide holiness to approach God’s house. Rather, he has a new habitat in our communities wherever we find ourselves. Those Jewish Christians remind us that our holiness, our community-wide efforts to suppress sin and repair brokenness, is what grounds our confidence to approach God.

It’s right and good that we don’t always feel close to God. Why should we? But the desire to feel his closeness, especially when it’s dulled by depressive states or frenetic lives of distraction, is also right and good. The answer is not to work ourselves up to some heightened state of God-detecting. Rather, it is to maintain the rhythms of our presence and our work in God’s promised habitat: his people gathered and awaiting his physical return to be present with the resurrected saints.

Image created by Rubner Durais

Did you enjoy this article? Check out The Biblical Mind podcast.