Who Is the Steward of Eden? Genesis and Environmental Stewardship

Adapted from her book on environmental stewardship, Stewards of Eden by Sandra L. Richter. Copyright (c) 2020 by Sandra L. Richter. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, PO Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60559. www.ivpress.com

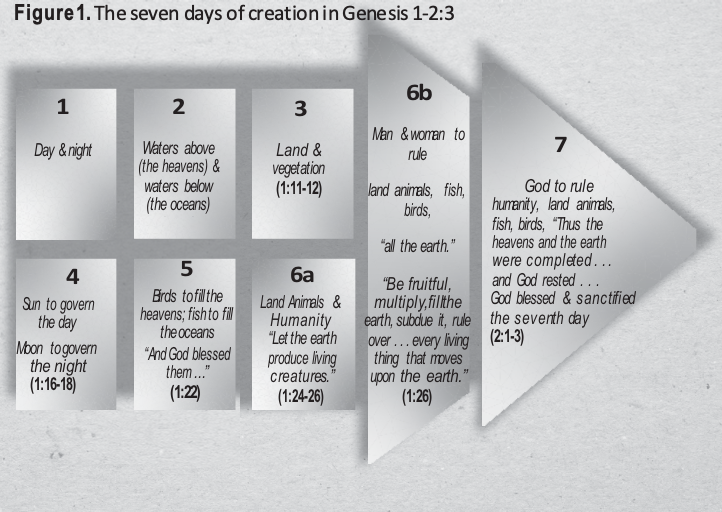

In the opening chapter of Genesis, God reveals his blueprint for creation. A close reading demonstrates that the questions the biblical author is attempting to answer are: “Who is God? What is humanity? And where do we all fit within this cosmic plan?” In figure 1, we see that the reader is offered an answer to these questions via the literary framework of a perfect “week.” Here the interdependence of the cosmos is laid out within seven days of creative activity, crowned by the final day, the Sabbath.

Thus, on days one through three we are offered three habitats (or kingdoms): (1) the day and night, (2) the sea and heavens, and (3) the dry land. On days four through six, the inhabitants (or rulers) of these various realms of creation are put in their proper places: (4) the sun and moon to rule the day and night, (5) the fish and birds to occupy the sea and sky, and (6a) the creatures who inhabit the dry land.1See Sandra Richter, The Epic of Eden: A Christian Entry into the Old Testament (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2008), 92–118; Meredith G. Kline, Kingdom Prologue: Genesis Foundations for a Covenantal Worldview (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2006), 38–43.

The relationship between the first three and last three days of Genesis’s creation song communicates place and authority. Thus, on day four God creates the “two great lights” to “govern” (or “be lord of”; Hebrew māšal) the day and night (Gen 1:14–19). On day five fish and birds are created to “be fruitful, multiply, and fill” the seas and skies (Gen 1:20–23). On day six the land creatures are created to occupy the dry land (Gen 1:24–25).

But as we approach the sixth day, we find that the literary structure of the piece shifts dramatically. Even the most casual reader can see that this day is given the longest and most detailed description up to this point. Why so much attention? Because this penultimate climax of Genesis 1 offers us the most breathtaking aspect of the Creator’s work so far. On this day a creature is fashioned in the likeness of the Creator himself—humanity (ʾādām) is created in the image of God:

Enjoying this article? Read more from The Biblical Mind.

Then God said, “Let us make humanity [ʾādām] in our image [ṣelem], according to our likeness; so that they may rule [Hebrew rādâ]2HALOT, s.v. “רדה” (1190). Although most often translated “to rule,” the argument has been made that “the basic meaning of the verb . . . actually denotes the traveling around of the shepherd with his flock” (ibid.; cf. Lev 25:43, 46, 53; Num 24:19; and 1 Kings 5:4). over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.” (Gen 1:26)

The profound implications of humanity (ʾādām) being fashioned and animated as God’s physical representatives on this planet cannot be overstated.3See Catherine McDowell, The Image of God in the Garden of Eden: The Creation of Humankind in Genesis 2:5–3:24 in Light of the mīs pî, pīt pî, and wpt-r Rituals of Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, Siphrut 15 (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2015), and Sandra L. Richter, The Epic of Eden: Isaiah, A One Book Curriculum (Franklin, TN: Seedbed, 2016). Both the biblical text and its ancient Near Eastern counterparts make it clear that for humanity to be named a ṣelem (image) is for humanity to be identified as the animate representation of God on this planet.

Imago Dei and Environmental Stewardship

In essence, woman and man are the embodiment of God’s sovereignty on earth. Here male and female are appointed as God’s custodians, his stewards over a staggeringly complex and magnificent universe, because they are his royal representatives. Like the fish and birds, humanity is commanded to “be fruitful, multiply, and fill” their habitat. But because they are the image bearers of the Almighty, they are also commanded to “take possession of” (Hebrew kābaš), and “rule” (Hebrew: rādâ) all of the previously named habitats and inhabitants of this amazing ecosphere as well:

God blessed them; and God said to them, “Be fruitful, multiply, and fill the earth so that you may take possession of it [kābaš].4HALOT, s.v. “כבש” (46). “Subjugate” is a typical translation of this verb. It is found throughout the Bible in contexts in which a people group or conquering army has moved into new territory and taken possession of it (e.g., Num 32:22, 29; Josh 18:1; 2 Sam 8:11). For example, David asks his cabinet, “Has God not given you rest on every side? For He has given the inhabitants of the land into my hand, and the land is subdued [kābaš] before the Lord and before His people” (1 Chron 22:18 NASB). This verb is typically used regarding land, not animate creatures. Rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the heavens and every living thing that moves on the earth.” (Gen 1:28)

In the language of covenant, Yahweh has identified himself as the suzerain, ʾādām as his vassal, and Eden as the land grant offered to ʾādām. The final stanza introduces the ultimate climax of both the week and the message—the Sabbath day (Gen 2:1–3). This seventh day is set apart; it is sacred; it is holy. This day communicates that the universe is finished, that the Creator is pleased. Most important to us, the seventh day answers the question, “Who is in charge here?” The answer? The perfect balance of this splendid and synergetic system is dependent on the sovereignty of the Creator.5See Kline, Kingdom Prologue, 38.

And as God is enthroned on the seventh day, humanity’s installation on the sixth day announces that man and woman have been appointed as God’s stewards. This message is reiterated in Psalm 8, when a worshiper standing millennia beyond the dawn of creation reiterates the wonder of humanity’s position in the cosmos:

When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers,

the moon, and the stars that you have fixed in place. What is humanity that you

should remember him? Or the son of ʾādām that you should care for him? You have

made them [humanity]

a little lower than the angels

and crowned them with glory and splendor,

You have made them lord [Hebrew māšal]6HALOT,s.v. “משל” (647-48); when combined with the preposition ְב this verb communicates placing someone into an office of authority (Dan 11:39). over the works of your hands,

You have placed everything under their feet Flocks and oxen, all of them!

Even the wild creatures of the field!

The birds of the heavens, and the fish of the sea, whatever passes through the paths of the seas! O Yahweh, our Lord,

how majestic is your name in all the earth. (Ps 8:3–9)

The message in both texts is explicit. Whereas the ongoing flourishing of the created order is dependent on the sovereignty of the Creator, it is the privilege and responsibility of the Creator’s stewards (that would be us) to facilitate this ideal plan by ruling in his stead. Like the other inhabitants of the earth, sky, and sea, the children of Adam are to “be fruitful, multiply, and fill” the earth. But as the ones made in God’s image, we are also given authority over land, sea and sky and all their creatures. And like any vassal who has been offered a land grant,7Richter, Epic of Eden, 69–91. humanity is commanded to “take possession” of this vast universe per the instructions of his sovereign lord (Gen 1:28).8For kābaš utilized with a land grant, see n. 3 as well as Josh 18:1 and 2 Sam 8:11. In sum, humanity has been created as God’s representative to serve as custodian and steward. We rule as he would rule. We are stewards, not kings.

Genesis 2:15 specifies humanity’s task further:

Then Yahweh Elohim took the human and put him into the garden of Eden to tend it [lĕʿobdâ]9s.v. “עבד” (773). The most essential meaning of this verb is “to serve; to work.” When in the context of cultivatable land, it is typically translated “to till”; when with an animal, “to work with.”and to guard it [lĕšomrâ].10HALOT, s.v. “שמר” (1581-84).

In this second creation account, the message is repeated: the garden belongs to Yahweh, but human beings have been given the privilege to rule and the responsibility to care for this garden under the authority of their divine lord. This was the ideal plan—a world in which humanity would succeed in building their civilization by directing and harnessing the amazing resources of this planet under the wise direction of their Creator. Here there would always be enough. Progress would not necessitate pollution. Expansion would not require extinction. The privilege of the strong would not demand the deprivation of the weak. And humanity would succeed in this calling because of the guiding wisdom of their God. We were designed to love what God loves, and we were commissioned to seek the stars.

But we all know the story: humanity rejected this perfect plan and chose autonomy instead. And because of humanity’s position within the created order, all creation paid the price for humanity’s choice. Because of ʾādām, “the creation was subjected to futility” (Rom 8:20),11See Douglas J. Moo and Jonathan A. Moo, Creation Care: A Biblical Theology of the Natural World (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2018), 147-52, for further discussion. “unable to attain the purpose for which it was created.”12Douglas J. Moo, “Nature in the New Creation: New Testament Eschatology and the Environment,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 49 (2006): 461. As I discuss in my book The Epic of Eden: A Christian Entry into the Old Testament, the curse enacted by humanity’s rebellion is not simply a list of random penalties—it is a reversal of God’s original blessings.13Sandra Richter, Stewards of Eden: What Scripture Says about the Environment and Why It Matters (Downers Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2020), 5–14. Those made in the image of God will now die like the animals. The earth, designed to serve, will now devour (Gen 3:19). The act of birth will now produce death (Gen 3:16). Adam’s labor, which was intended to bring security to his family, will now be undermined by the very resources designed to provide for him (Gen 3:17-19). In other words, the perfect balance of Eden, portrayed in the seven-day structure of Genesis 1, has been flipped upside down. And the treason of God’s chosen stewards has consigned all under their authority to frustration and death. In an instant, God’s perfect world became ʾādām’s broken world—full of conflict, want, death, anxiety, and violence.

Caring for the Fallen Earth

In his Epistle to the Romans, Paul reflects on the impact of humanity’s sin on the cosmos and the glory of the world to come.

For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory that is to be revealed to us.19 For the anxious longing of the creation waits eagerly for the revealing of the sons of God.20 For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of Him who subjected it, in hope21 that the creation itself also will be set free from its slavery to corruption into the freedom of the glory of the children of God.22 For we know that the whole creation groans and suffers the pains of childbirth together until now.23 And not only this, but also we ourselves, having the first fruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting eagerly for our adoption as sons, the redemption of our body. (Rom 8:18–23 NASB)

Paul speaks of all creation anxiously longing for “the revealing of the sons [heirs] of God” (Rom 8:19). Why does creation wait? Because “creation has been unable to attain the purpose for which it was created.” The ʾădāmâ (the “ground” in your translation) was subjected to ineffectiveness because of the rebellion of ʾādām (do you see the word play?). God’s chosen steward rebelled against his sovereign and so the Garden has rebelled against him, and is now trapped in the same self-defeating cycle as we are—“slavery to corruption” (v. 21).

So just like the heirs of the kingdom, creation awaits its deliverance—a poignant presentation of the great arc of redemptive history. As I often tell my students, redemption isn’t just about getting you or me into heaven. Redemption is about restoring all creation. When the Last Adam returns, the chaos of the first ʾādām’s rebellion will be redeemed—the curse lifted, the cosmos liberated, and the earth healed from the effects of humanity’s sin (1 Cor 15:45). God’s ideal design for creation, as detailed in Genesis 1, will be restored. This very earth is the “New Earth” we hope for—healed of its scars and washed clean of its diseases just like the resurrected children of Adam (Rom 8:22-23). In other words, the redemption of this planet is built into the master plan.

The epic of Israel advances the same story. Like Eden, the “promised land” is a land grant—a fiduciary trust. The Mosaic covenant required that the flora and fauna of that land be stewarded with care. Sustainable agriculture was required.14Sandra Richter, Stewards of Eden: What Scripture Says about the Environment and Why It Matters (Downers Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2020), 5–14. Exploitation of the wild creature or its habitat was forbidden.15Ibid., 48–59. Abuse of the domestic creature was prohibited.16Ibid., 29–47. Environmental terrorism was banned.17Ibid., 60–66. Short term, desperation management that exhausted current resources in answer to the cry of the urgent was simply not acceptable in the theocratic government of ancient Israel. Even though this nation spent most of its existence on the razor’s edge of a subsistence economy, where the margin between “enough” and starvation was often imperceptible. Israel’s obedience to these covenantal mandates resulted in not only their personal economic success, but the long term care of the widow and the orphan as well.18Ibid., 67–81. We are therefore forced, as the heirs of Abraham and the kin of the Christ, to ask ourselves, “If this was Eden’s ideal and Israel’s law what should ours be?”

In my experience, the community of faith readily recognizes the disastrous effects of the fall in the arena of human relationships. Corrupt and abusive governments, bigotry and violence, the oppression of the weak and the deprivation of the voiceless—no one needs to tell us that these realities were not God’s original intent. Nor, in my experience, does anyone need to tell the committed believer that it is the responsibility of the community of faith to take a proactive stand against these distortions of God’s good plan. But rarely, it seems, do we as believers reflect on the effects of humanity’s rebellion on the garden. And rarely, it seems, do we consider how the reality of redemption in our lives should redirect our attitude toward the same.

End Notes

1. See Sandra Richter, The Epic of Eden: A Christian Entry into the Old Testament (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2008), 92-118; Meredith G. Kline, Kingdom Prologue: Genesis Foundations for a Covenantal Worldview (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2006), 38–43.

2. HALOT, s.v. “רדה” (1190). Although most often translated “to rule,” the argument has been made that “the basic meaning of the verb . . . actually denotes the travelling around of the shepherd with his flock” (ibid.; cf. Lev 25:43, 46, 53; Num 24:19; and 1 Kings 5:4).

3. See Catherine McDowell, The Image of God in the Garden of Eden: The Creation of Humankind in Genesis 2:5–3:24 in Light of the mīs pî, pīt pî, and wpt-r Rituals of Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, Siphrut 15 (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2015), and Sandra L. Richter, The Epic of Eden: Isaiah, A One Book Curriculum (Franklin, TN: Seedbed, 2016).

4. HALOT, s.v. “כבש” (460). “Subjugate” is a typical translation of this verb. It is found throughout the Bible in contexts in which a people group or conquering army has moved into new territory and taken possession of it (e.g., Num 32:22, 29; Josh 18:1; 2 Sam 8:11). For example, David asks his cabinet, “Has God not given you rest on every side? For He has given the inhabitants of the land into my hand, and the land is subdued [kābaš] before the Lord and before His people” (1 Chron 22:18 NASB). This verb is typically used regarding land, not animate creatures.

5. See Kline, Kingdom Prologue, 38.

6. HALOT,s.v. “משל” (647-48); when combined with the preposition ְב this verb communicates placing someone into an office of authority (Dan 11:39).

7. Richter, Epic of Eden, 69–91.

8. For kābaš utilized with a land grant, see n. 3 as well as Josh 18:1 and 2 Sam 8:11.

9. s.v. “עבד” (773). The most essential meaning of this verb is “to serve; to work.” When in the context of cultivatable land, it is typically translated “to till”; when with an animal, “to work with.”

10. HALOT, s.v. “שמר” (1581-84).

11. See Douglas J. Moo and Jonathan A. Moo, Creation Care: A Biblical Theology of the Natural World (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2018), 147-52, for further discussion.

12. Douglas J. Moo, “Nature in the New Creation: New Testament Eschatology and the Environment,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 49 (2006): 461.

13. Moo, “Nature in the New Creation,” 461. “The ‘vanity’ to which creation was subjected would appear to refer to the lack of vitality which inhibits the order of nature and the frustration which the forces of nature meet with in achieving their proper ends” (Murray, Epistle to the Romans, 303); cf. William Sanday and Arthur C. Headlam, The Epistle to the Romans, 4th ed., International Critical Commentary (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1900), 205.

14. Sandra Richter, Stewards of Eden: What Scripture Says about the Environment and Why It Matters (Downers Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2020), 5–14.

15. Ibid., 48–59.

16. Ibid., 29–47.

17. Ibid., 60–66.

18. Ibid., 67–81.

Subscribe now to receive periodic updates from the CHT.