How the Ten Commandments Shape the Moral Imagination

Late Second Temple and New Testament era debates about divorce often focused on the seemingly strange law discussing divorce in Deuteronomy 24 (e.g., m. Gittin; Matt 19:1–9). Modern debates about divorce often feature that passage too. But that law is notoriously complicated.

Enjoying this article? Read more from The Biblical Mind.

It describes a woman divorced by her first husband and given a “certificate of divorce;” later married to another man; then separated from her second husband with, potentially, another “certificate of divorce;” and finally desired back by the first husband—who is barred from remarrying her (Deut 24:1–4). What in the world is that all about?

As we will see, this law is not about divorce at all! It is an example of an ancient Near Eastern form of law-writing scholars call “wisdom law.”1The term “wisdom laws” was coined by Bernard Jackson. His masterful introduction to the concept of wisdom laws can be found in Bernard Jackson, Wisdom-Laws: A Study of the Mishpatim of Exodus 21:1–22:16 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), esp. chapters 1–2. A mini-narrative is crafted to capture a moral principle that may have little to do with the specifics of the illustration itself. It is an approach to law designed not to regulate the courtroom but to shape the people’s moral imagination.

The book of Deuteronomy is a remarkable example of such wisdom laws. Modern readers often mistake Deuteronomy as a reference book for rote application by ancient judges facing specified situations, like modern law books. Instead, we should view Deuteronomy as a series of thought exercises expounding the Ten Commandments through paradigms that form a people in moral wisdom.

The Shape of Deuteronomy

Here is a riddle. It’s a very old one from ancient Sumer. See if you can solve it:

Whoever enters it has closed eyes.

Whoever departs from it has eyes that are wide open.

What is it?

When you are ready, the answer is in this footnote.2The expected answer of this riddle is “a school.” James L. Crenshaw, Education in Ancient Israel: Across the Deadening Silence (New York: Doubleday, 1998), 116.

Did you solve it? This riddle is actually a statement about education.

The process of schooling may look different today than in the ancient world. But teachers ancient and modern share the same goal: to open their students’ eyes. Instruction is not just about filling heads with information to regurgitate. It is helping students see, think, and solve problems even where answers are not obvious—in short, it is helping students become wise and develop moral imagination.

In the book of Deuteronomy, Moses wanted to train Israel to be wise (Deut 4:1–6) since he was about to leave them. The people would enter the Promised Land, but Moses was about to die. So he poured out his heart in one final series of lessons to equip the people to settle the land without his guiding presence.

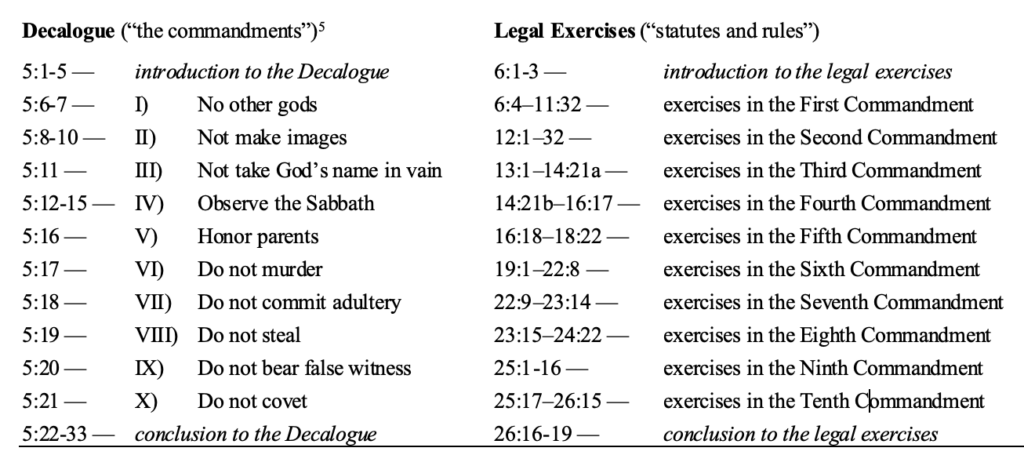

The prophet’s class began with a recitation of the Ten Commandments (5:6–21). The people had previously received those commands directly from the voice of God (5:4). After repeating the Decalogue, Moses launched into a series of “statutes and rules” which “the Lord your God commanded me to teach you” (6:1–26:19). These “statutes and rules” were legal thought exercises expounding each of the Ten Commandments, one at a time.

Many scholars have recognized that the statutes in the body of the book are topically organized according to the Ten Commandments.3This approach was first suggested by Friedrich Wilhelm Schultz, Das Deuteronomium (Berlin, 1895), and was introduced into current scholarship by Stephen Kaufman, “The Structure of the Deuteronomic Law,” Maarav 1/2 (1978–1979), 105–58, and Georg Braulik, “Die Abfolge der Gesetze in Deuteronomium 12–26 und der Dekalog,” in Das Deuteronomium: Entstehung, Gestalt und Botschaft (Louvain: Louvain University Press, 1985), 252–72, followed by others. This view is still debated and is not universally accepted. There are difficulties with the thesis, but the case is growing stronger as new evidence emerges to support it.4My own recent arguments are in Michael LeFebvre, “The Decalogical Shape of the Deuteronomic Law Collection,” in Exploring the Composition of the Pentateuch, vol. 3, eds. Kenneth Bergland, Roy Gane, Benjamin Kilchör and A. Rahel Wells (forthcoming).

In most sections of the book, the coordination of grouped statutes and the related commandment is clear. For example, the lengthy section beginning with the Great Shema (“Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one”) contains numerous exhortations on exclusive fidelity to Yahweh (6:4–11:32), matching the concerns of the First Commandment (“You shall have no other gods before me”).

Likewise, the concerns of the Sixth Commandment (“You shall not murder”) are present throughout Deuteronomy 19:1–22:8—a section with guidance to distinguish accidental manslaughter from intentional murder (19:1–13), laws on just and unjust killing in warfare (20:1–20), instruction for handling unsolved murders (21:1–9), and so on.

The Ten Commandments are a succinct summary of all moral goodness, and the book of Deuteronomy is a series of practice exercises to unpack the wisdom contained in them. But some of the connections between Deuteronomy’s statutes and the corresponding commandments are not clear—until we learn to read them as wisdom laws.

Moral Imagination and the Nature of Deuteronomy’s Laws

The genius of Moses’ curriculum is in the nature of the laws he gives. These statutes are not narrow rulings for precisely defined circumstances. They are broad and provocative learning paradigms, more like proverbs that cultivate moral imagination than what we now think of as laws. In fact, some of his laws are legal proverbs.

Consider a pair of laws in Deuteronomy 22:9–10: “You shall not sow your vineyard with two kinds of seed, lest the whole yield be forfeited, the crop that you have sown and the yield of the vineyard. You shall not plow with an ox and a donkey together.”

These are wise business practices—and obviously so. Israel did not need laws to regulate these problems, since these are not really problems Hebrew farmers would face. There is no temptation to plant grain in the same field with grapes! Grapes and grain grow differently, mature at different seasons, and require different harvesting methods. To swing a sickle among grain stalks that are intertwined with grape vines would be disastrous for both. Likewise, there is no reason any Hebrew farmer would yoke an ox with a donkey; both animals would be harmed and the field would not be plowed.

As a teacher of wisdom, Moses uses these legal proverbs to begin his section of rules on Seventh Commandment themes: “You shall not commit adultery” (5:18; 22:9–23:14). The teacher is not regulating farming practices here. He is using obvious agricultural follies to shape our thinking about sexual integrity. When fidelity is flouted everyone suffers—as both grain and grapes are lost and both ox and donkey are harmed in these hypotheticals. On the surface, these farming laws do not appear to be about the Seventh Commandment. But they actually are. And they train us to think more broadly than their specific scenarios.

Not all of Moses’ laws are proverbial. Some address real situations. But even these are crafted for broader application than the circumstances stated. For example, we encounter this rule in the section about the Eighth Commandment (“You shall not steal”): “You may charge a foreigner (nākrî) interest, but you may not charge your brother interest” (23:19-20).

Read narrowly, this sounds like ethnic prejudice. But read as a wisdom law, we reflect on the stereotype the scene evokes for broad application. In this case, the contrast is not based on ethnicity: it is not a Hebrew settler and a Gentile settler (a “sojourner,” gēr). The term used (nākrî) suggests, in this context, a foreign trader whose desire for a loan is contrasted to that of a needy neighbor.5Michael Guttmann, “The Term ‘Foreigner’ (nkry) Historically Considered,” HUCA 3 (1926), 4–7. From this contrast we learn that interest on a business loan is fair, but imposing interest on loans to the poor—making money off another’s misfortune—is a form of stealing. The implication of the law is much broader and more conceptual than the scenario used to teach it.

How the ‘Divorce Law’ Teaches Economic Honesty

What about that complicated “divorce law” in Deuteronomy 24? Here is that law in full, displayed here to show its if-then construction:

When a man takes a wife and marries her,

IF then she finds no favor in his eyes because he has found some indecency in her, and he writes her a certificate of divorce and puts it in her hand and sends her out of his house, and she departs out of his house, and

IF she goes and becomes another man’s wife, and the latter man hates her and writes her a certificate of divorce and puts it in her hand and sends her out of his house, or if the latter man dies, who took her to be his wife,

THEN her former husband, who sent her away, may not take her again to be his wife, after she has been [declared] defiled, for that is an abomination before the Lord. And you shall not bring sin upon the land that the Lord your God is giving you for an inheritance. (24:1-4)

This law is strangely specific. How often would Israel face this rather remarkable situation? Furthermore, the law tells a story about divorce, but it never offers imperatives about divorce. That is because the law is not really about divorce at all. Divorce is just the story used. This is a law about economic honesty, which is why it appears among Deuteronomy’s reflections on the Eighth Commandment.

In the ancient world, the purpose of a “certificate of divorce” was to document the property that a woman retained after divorce. In the first scenario, the husband divorces the woman because of a fault in her (“he found some indecency in her”). She was the guilty party, so she would have been released empty-handed. In that scenario, the husband profited by divorcing her, keeping her dowry for himself as documented in her certificate.

In the second scenario, the woman was divorced due to the displeasure of the man or was single again on account of his death. Those scenarios share the common result that the woman would retain her dowry and inheritance rights. The second certificate documents the woman’s retained property. Suddenly her original husband has renewed interest. But this law forbids the man from suddenly declaring the woman eligible for marriage whom he before conveniently “[declared] defiled.”

This is not really a law about divorce. It is a law about changing one’s opinion to suit present economic advantage,6For further discussion about this law: Raymond Westbrook, “The Prohibition on Restoration of Marriage in Deuteronomy 24:1-4,” in Sara Japhet, ed., Studies in Bible (Scripta Hie rosolymitana 31; Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1986), 387–405. like claiming ownership of a piece of real estate when it is valuable, but denying ownership when it becomes a liability. In modern law, we use the term “estoppel” to address such inconsistent claims. Moses’ law uses a very specific (extremely unlikely!) example to teach a much broader lesson. It is a wisdom law designed to stir our imagination about the nature of justice in all kinds of economic dilemmas.

Thought Exercises for Today

Today, there is a growing interest in Old Testament law. Recent scholarly breakthroughs in the understanding of ancient Near Eastern law are fueling renewed attention to the role of biblical law in churches, synagogues, and classrooms. It is exciting to see.

One frontier of these developments is to rediscover the character of Deuteronomy as a wisdom text for all times to shape moral imagination, rather than a law code for ancient judges. Biblical law is more like ancient proverbs and less like modern legislation than we have generally realized.

The Decalogue, in particular, presents a grand vision for human society in ten simple strokes. And Deuteronomy helps us unpack those ten succinct commands through a series of thought exercises to make us wise. It is a wisdom curriculum that remains useful to shape us to love God and love our neighbors well, even today.

End Notes

1. The term “wisdom laws” was coined by Bernard Jackson. His masterful introduction to the concept of wisdom laws can be found in Bernard Jackson, Wisdom-Laws: A Study of the Mishpatim of Exodus 21:1–22:16 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), esp. chapters 1–2.

2. The expected answer of this riddle is “a school.” James L. Crenshaw, Education in Ancient Israel: Across the Deadening Silence (New York: Doubleday, 1998), 116.

3. This approach was first suggested by Friedrich Wilhelm Schultz, Das Deuteronomium (Berlin, 1895), and was introduced into current scholarship by Stephen Kaufman, “The Structure of the Deuteronomic Law,” Maarav 1/2 (1978–1979), 105–58, and Georg Braulik, “Die Abfolge der Gesetze in Deuteronomium 12–26 und der Dekalog,” in Das Deuteronomium: Entstehung, Gestalt und Botschaft (Louvain: Louvain University Press, 1985), 252–72, followed by others.

4. My own recent arguments are in Michael LeFebvre, “The Decalogical Shape of the Deuteronomic Law Collection,” in Exploring the Composition of the Pentateuch, vol. 3, eds. Kenneth Bergland, Roy Gane, Benjamin Kilchör and A. Rahel Wells (forthcoming).

5. Michael Guttmann, “The Term ‘Foreigner’ (nkry) Historically Considered,” HUCA 3 (1926), 4–7.

6. For further discussion about this law: Raymond Westbrook, “The Prohibition on Restoration of Marriage in Deuteronomy 24:1-4,” in Sara Japhet, ed., Studies in Bible (Scripta Hie rosolymitana 31; Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1986), 387–405.