Part of the 6 Jewish Thinkers All Christians Should Know series

Yoram Hazony: How the Bible Bridges the Reason–Revelation Divide

The Bible’s important messages for human flourishing are obvious. The centrality of human freedom in the Exodus story or the perniciousness of envy as the impetus for Cain’s murder of Abel illustrate this orientation. There is, however, a culturally imposed divide between reason and revelation that limits the reach of the biblical worldview.

Enjoying this article? Read more from The Biblical Mind.

Too often, people view the Bible as a work of revelation that stands in opposition to human reason. When biblical commands conflict with the contemporary ethics that are developed by human reason, the reason–revelation framing forces people to choose between what they perceive as faith-based or even absurd, and that which they perceive as reasonable.

Yoram Hazony’s philosophical approach to the Bible offers a third option. He interprets the Bible as a divinely revealed book of reason and in so doing makes the Bible deeply relevant to understanding the human condition and the life well-lived.

Hazony—philosopher, Bible scholar, political theorist, and President of the Herzl Institute—observed in his The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture that the Hebrew Bible is mainly concerned with the

histories of ancient people and attempts to draw political lessons from them; explorations of how best to conduct the life of the nation and individual; . . . the search for the true and the good; attempts to get beyond the here and now and to try and reach a more general understanding of the nature of reality.

Furthermore, “there are no texts in the Hebrew Scriptures in which God’s word is referred to as ‘foolishness or ‘absurd,’” Hazony said. Though humans may not grasp the purpose of God’s commands, the Bible contends that “the word of God is itself precisely the wisdom that is sought by human beings for the present, human world.” It defines right and wrong and lays out first principles.

Relegating the Hebrew Bible to what “make[s] sense to God,” which “requires the suspension of the normal operation of our mental faculties” misunderstands the purpose of the Bible, Hazony explains. Explicit works of reason, where humans use their faculties to systematically determine what is true and good in life, only begins to be written in Greece in the sixth century BCE. At this point, the Kingdom of Israel had already reigned for a while and been destroyed, and the Kingdom of Judah is on its last leg. As far as we know, Israel had no contact with the Greek city-states. By the time Alexander the Great conquered the Levant, bringing Greek philosophy with him, the books of the Hebrew Bible had already been written. Simply put, the Hebrew Bible predates the dichotomy between reason and revelation and offers a more holistic view.

The Hebrew Bible predates the dichotomy between reason and revelation and offers a more holistic view.

The Bible’s own self description claims a more integrated vision: God’s commands are “wisdom and insight in the eyes of the other nations” (Deuteronomy 4:6). In its understanding of itself, reason and revelation are in consonance. According to Hazony, therefore, the widely held view that the Bible is a work of revelation and in opposition to reason creates a “distorting lens” and “accidentally delete[s] much of what these texts were written to say.”

When the Bible addresses core philosophical concerns, it distinguishes itself in conception and in its method of philosophical exploration.

Key Differences between Hebraic and Greek Philosophy

Before covering some specific ways that the Torah communicates its philosophical approach to life, we should first recognize that it disagreed with Greek thought at the most basic understanding of knowledge and reality. It perceives life differently and uses similar words to mean different things.

Hebraic Truth vs. Greek Truth

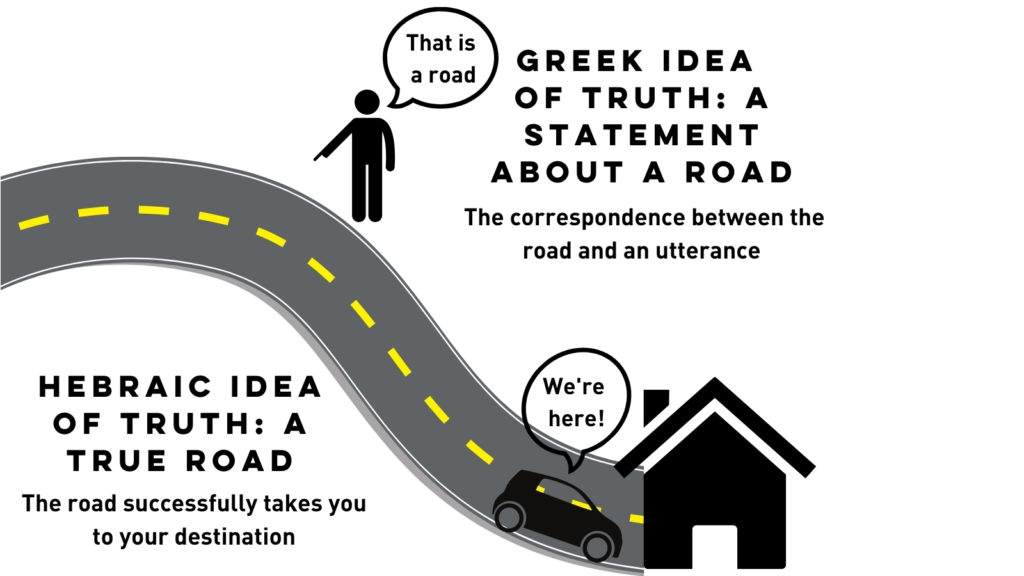

One basic epistemic (i.e., relating to knowledge) difference between the Bible and Greek thought is how they each understand truth and falsehood. Aristotle’s definition of truth (Metaphysics 1011b25) focuses on how speech describes the nature of things, say a chair or a circle. Speech is true when it describes the unchanging essential form of an object. This perfect object exists in an independent theoretical dimension. In the Greek conception, articulation and accuracy are the key factors in determining truth and falsehood.

By contrast, truth (emet/אמת) in the Hebrew Bible relates to the “quality of objects,” not words. Roads, people, and grape seeds are described as true, while physical attraction and the safety of a horse are labeled as false. Used in this way, truth describes objects that can be relied upon. These truthful items will consistently perform as they ought to, “despite the hardships thrown up by a changing circumstance,” Hazony wrote.

For example, pointing to a street and claiming that it is a street because it is paved, located between houses, for the public to use, and for cars to drive on is a true statement in Greek thought. The emphasis is on speech and on its similarity to the ideal form of a street. The Hebrew Bible in contrast, offers a more pragmatic understanding of truth. The road itself can be called true, and its trueness consists in its properly getting the traveler to the desired destination. There are no idealized forms and reality can change to better suit people’s needs.

Speech, Thought, and Objects

There is a similar distinction in the usage of the word “speech” (davar/דבר). For Aristotle, “speech” is limited to the spoken word. In the Hebrew Bible, davar’s primary usage is for speech as well, and corresponds with the oft-repeated verse “God spoke to Moses,” where the verb Vayidaber (וידבר) is used. At the same time, the Bible uses the word davar (דבר) to refer to a “thing” in the generic sense, including unspoken logical thoughts, material objects, or other legal matters and human events.

The integral continuum among speech, thoughts, and objects found throughout the Bible goes hand in hand with its conception of truth and falsehood. The Greek approach promotes a dualism, where the ideal, static, and perfect forms of objects exist in a separate, abstract dimension that can only be described with words.

The Bible, however, rejects dualism. Truth and davar relate to rules for life in this holistically integrated, unified world. The Greek conception inclines toward shaping the reality here (both objects and humans) towards theorized forms that remain separate, and possibly detached, from reality. In contrast, the Bible encourages an ethical empiricism, urging humans to conform to the already existing rules of reality, which have proven themselves time and again (and whether we like it or not).

Key Differences between Greek and Hebraic Approaches to Reasoning

Since Greek thought understood truth to be conveyed through speech, it endeavored to teach its ideals with pure language. Aristotle’s Metaphysics Book XII, for example, begins by defining terms, while others like Plato’s The Phaedrus teach the nature of things through extensive dialogue.

The Bible’s aversion to pure speech means that we would expect to find a different approach to conveying philosophical ideas, and indeed we do.

Reasoning through Narrative

The Hebrew Bible never defines words in extended form (though it does define foreign words, like Esther 3:7), and its longest dialogue is a mere 36 verses (Exodus 3:4–4:17). Ironically, that conversation is not about an idea, but about convincing Moses to lead Israel out of Egyptian bondage. Instead, the Bible’s empiricist approach uses narratives about human actions and their consequences to teach what Leon Kass termed in The Beginning of Wisdom “not what happened, but what always happens.” In this way, the history section of the Bible uses stories to convey its philosophy, rather than pure speech.

The Bible’s empiricist approach uses narratives about human actions and their consequences to teach what Leon Kass termed in The Beginning of Wisdom “not what happened, but what always happens.”

At the same time, conversations about morality are terse, such as the two verse conversation between Jacob and his sons regarding the proper response to Dinah’s rape. The brothers want justice, while Jacob wants peace, and this significant argument is expressed very concisely, while communicating complexity:

Then Jacob said to Simeon and Levi, “You have brought trouble on me by making me stink to the inhabitants of the land, the Canaanites and the Perizzites. My numbers are few, and if they gather themselves against me and attack me, I shall be destroyed, both I and my household.” But they said, “Should he treat our sister like a prostitute?” (Gen. 34:30–31, ESV)

Furthermore, Bible stories employ sophisticated literary techniques to present profound ideas. One method is its contrast of character types. For example, Cain represents farmers, while Abel shepherds. Cain is also the first city builder and murderer. In the ancient world, wealth was accumulated through farming via massive irrigation projects. This required turning “populations [into] slaves for periods of weeks or months when important projects were under way.” As more land became arable, more wealth was accumulated. The critical lesson is that ostensibly, organization of resources and authority over people produces the greatest benefits.

This wealth was used to construct cities and magnificent edifices such as pyramids and ziggurats. The same principles of organization and authority were employed. Just as the people were enslaved to build essential irrigation, they similarly built the cities and towers. Ensuring discipline necessitated a large bureaucracy, while a large army was needed to protect all that they had built. Not surprisingly, the king’s immense wealth in contrast to his subjects’ poverty transformed him into a god-figure, built on the back-breaking work of others, and commanding the actions of others. Given the farmer’s dehumanization inclination, it is also not surprising that the farmer is the Bible’s first murderer, and cities, like Sodom, are places of human cruelty.

In contrast, Abel represents the shepherd. Rather than follow his father and older brother into the world of farming, Abel uses his entrepreneurial spirit to try his hand at a new profession. Even more remarkably, God commands Adam to be a farmer, but Abel takes God’s silence on other professions to try his hand at shepherding. In the end, God approves and communicates his desire for human independence and innovation.

While the farmer improves his lot through organization and authority, the shepherd, skeptical of hierarchy, employs creativity and independence to better his life.

The Bible, however, does not ignore the shepherd’s challenges, especially the vulnerability of a nomadic lifestyle. When famine arrives, as it frequently does, it is the farming civilizations that can sustain life. Similarly, the constant movement of the shepherd prevents him from forming larger communal bonds. Like Jacob as he approaches Esau, the shepherd lacks the consistent protection needed to ward off invading armies.

Shepherds, like Abraham, Jacob and Moses, are the Bible’s initial heroes, but it is the character of David who can take the virtues of the shepherd and bring them into the city when creating the national polity.

Through these typologies, the Bible communicates the virtues and drawbacks of different approaches to life. It endorses the benefits and warns about excesses. In this way, it recognizes that life is more complicated than the idealized types.

A similar usage of complex and nuanced typology is its depiction of leadership types. These are initially embodied by Jacob’s children. Reuben is protective and sentimental, Simon uses violence, Levi passionately pursues justice and purity, Judah has the ability to reflect and correct course to achieve the larger goal, while Joseph can “manipulate power in the service of some end.” These types repeat in Israel’s history. King David follows Judah’s model, and while ultimately successful, is mired in inconsistency and personal failure. His son and successor Solomon acts in Joseph’s mold and suffers the same fate; initial success in organizing and building loses sight of the larger vision and proves unsustainable.

Meanwhile, David’s predecessor Saul is a Reuben type leader who fails to lead and inspire. The Levi character is removed from political power to work in the Temple. At critical moments, like in the aftermath of the Golden Calf and with Phineas, the Levite steps forward to protect the covenant. The Simons are best used sparingly and in the right role like David’s general Yoav ben-Tzruia. Like the judge Jephthah, he may achieve salvation, but his violent streak will also emerge in destruction ways, like Jephthah civil war and Yoav’s murder of potential competitors.

Event Repetition

A second methodology for teaching Biblical philosophy is building upon earlier stories through the repetition of events. Gideon’s construction of a golden monument from earrings after his miraculous victory repeats the sin of the Golden Calf, built from earrings after the miraculous Exodus and revelation at Sinai. One might imagine that a newly freed people desires freedom, but Hazony points out that “this is an illusion. True freedom—in which a man stands on his own feet, responsible for his own actions, with nothing but the open sky between himself and God—is in such cases experienced as something terrifying and even dreadful.” Rather, the people crave “someone above them again.” These repetitions reflect something true about human nature.

God only gives Abraham a slice of land, not the whole world. The nation of Israel inherits detailed borders, and they are even forbidden from attacking certain other nations.

Similar recurring stories are: the Sodom (Gen. 19) and Concubine at Giva (Judges 19) stories, where the sexual exploitation of an outsider signals complete societal corruption; and the dangers of accepting too much hospitality as evidenced by Jacob’s and the nation of Israel’s subsequent enslavement.

Yoram Hazony’s Nationalism

In the last few years, Hazony has become well known for his The Virtue of Nationalism. Unlike other forms of nationalism, this particular nationalist vision stems directly from the Bible. Independent nations instead of an imperialist global order is the clear vision of the Hebrew Bible. Hazony cites numerous biblical texts to this effect. The Tower of Babel is an attempt to impose imperial rule, which God rebuffs by reimposing nations and difference.

God only gives Abraham a slice of land, not the whole world. The nation of Israel inherits detailed borders, and they are even forbidden from attacking certain other nations. Even the messianic visions of Isaiah and Zechariah insist on the existence of other nations. Israel never has imperialist ambitions. Even in its ideal, the global order is a type of nationalist one promoting human difference. Here too, the Bible has important ideas about ideal human living on earth.

Seeing the Hebrew Bible as a book of reason leads us to two important conclusions. First, it serves as a check and guide to ethics. Human reason has a long history of going awry, and the Hebrew Bible prevents these errors. Second, when revelation is viewed as in consonance with reason, it gives us a profound theological idea. The God of creation and revelation is fully invested in guiding humans to living life best and maximizing human potential.

Did you enjoy this article? Check out The Biblical Mind podcast.