Say You, Say Ye: Individual and Collective Identity and Responsibility in Torah

Torah freely interchanges “you” singular and plural in its legal standards. Torah’s alternation of second person singular and plural pronouns affirms the interrelated collective and individual identity of God’s people and spells out their associated collective and individual responsibilities. The present study limits its case studies to second person pronouns in Torah’s legal standards that concern the socially disadvantaged.

Enjoying this article? Read more from The Biblical Mind.

In previous studies I have pushed back against a longstanding either/or interpretive mindset with its argument that the older collective outlook of Israel was replaced by an individualistic focus.1See Gary Edward Schnittjer, Old Testament Use of Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, 2021), 834–39; cf. 279–81; 323–24; Gary Edward Schnittjer, “Individual versus Collective Retribution on the Chronicler’s Ideology of Exile,” Journal of Biblical and Theological Studies 4.1 (2019): 113–32. For other interaction with individual and collective perspectives in Scripture, see Gary Edward Schnittjer, Torah Story, 2nd edition (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, forthcoming), chap 24 ad loc; Gary Edward Schnittjer, “The Bad Ending of Ezra-Nehemiah,” Bibliotheca Sacra 173 (2016): 49–55 [32–56]. The present study seeks to extend attention to biblical evidence of a both/and collective and individual overlapping sense of identity and responsibility in Torah.

This study will note selected issues concerning singular and plural second person pronouns in the English Bible and Hebrew Bible, examples in Torah’s major legal collections regarding the socially disadvantaged, and selected implications.

Torah’s interchange of singular and plural second person pronouns in its legal collections pushes back against today’s strident commitment to self-autonomy. It does not merely present a collective identity in its place.

Thou and Ye

Second person pronouns in Torah’s legal collections have been vulnerable to readers of the English Bible and interpreters of the Hebrew Bible. While the trouble in the English Bible results in readerly insensitivity, the trouble in the Hebrew Bible stems from interpretive oversensitivity.

The case system of second person pronouns went extinct from written English long ago. Remnants remain within spoken English in certain local dialects of the United States, like the southern “y’all,” Appalachian “y’uns,” and Philadelphia-talk “yous guys.” Some local dialects can be very exacting, such as when a newcomer says, “You guys,” causing native Philadelphians to wince and roll their eyes.

Are moderns radical individualists? No one doubts this. But the solution is not to eradicate personal responsibility or even to replace personal identity with collective identity.

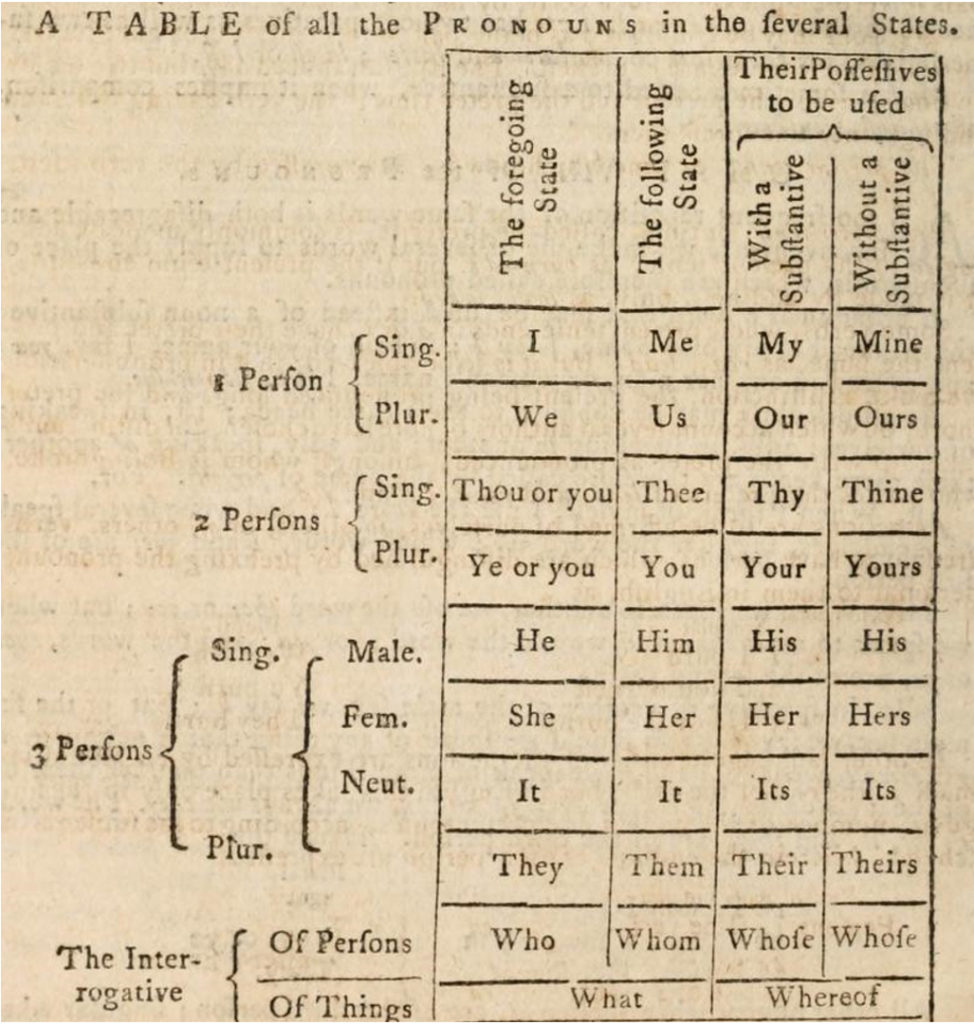

The loss of a case system for second person pronouns in modern English obscures the sense of legal instructions in Torah for English Bible readers. Older English translations, notably the Authorized King James Version, took advantage of the second person pronoun case system that was already passing away to translate more clearly the singular and plural referents of Scripture.

Thou and ye signified singular and plural second person subject pronouns. Meanwhile thee and you signified singular and plural object pronouns, and thy/thine and your/yours referred to singular and plural genitive functions. Thou, thee, and ye survived much longer than they would have otherwise, likely due to the King James Version, as can be seen in an English grammatical table of pronouns from the late eighteenth century.2Table of pronouns from D. Fenning, The Royal English Dictionary; or, a Treasury of the English Language, 4th ed. (London: Printed for L. Hawes and Co., 1771), 20 [public domain].

In spite of many interesting expressions, such as withersoever, hath, wouldest, and so on, most moderns who scorn older English translations complain about the thous, thees, and ye’s. Nearly all modern committee translations of the English Bible have accommodated readers’ tastes by flattening all second person subject and object pronouns to “you.”

The all-purpose “you” enables the tendency of today’s English Bible readers to interpret Scripture in radically individualistic ways. In any case, the use of the umbrella pronoun “you” obscures for English Bible readers pervasive shifts from thou to ye and from thee to you and vice versa across the legal instructions of Torah.

The constant shifts between singular and plural second person pronouns in Torah’s laws once provided many source-critical biblical scholars a rich set of opportunities. Some scholars argued that they could detect seams between contradictory sources of Torah by an alleged penchant for plural pronouns in one source and singular pronouns in the other. In this view, hapless ancient scribal redactors were forced to merge together incongruent plural and singular pronouns because of the authority already attached to the competing sources.

Meanwhile at the high-water mark of textual emendations of the biblical text, shifts between second person singular and plural pronouns offered abundant opportunities to “repair” the damage supposedly done by ancient clumsy scribes. The Biblia Hebraica series shifts from emendation-happy scholarship (BHK), to plentiful but more restrained emendations (BHS), to resisting emendations except when really necessary (BHQ).3Biblia Hebraica, ed. by R. Kittel, 3rd ed. (Stuttgart: Bibelanstalt, 1937), hereafter cited as BHK; Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, ed. by Karl Ellinger, Wilhelm Rudolph, et al., 5th ed. (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1997), hereafter cited as BHS; Innocent Himbaza, ed., Leviticus: Biblia Hebraica Quinta (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2020), hereafter cited as BHQ; Carmel McCarthy, ed., Deuteronomy: Biblia Hebraica Quinta (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2007), hereafter cited as BHQ. All translations of Biblia Hebraica are mine unless stated otherwise. All emphases added to translations are mine. Notice how the critical apparatus of this series shifts in its handling of the last pronouns of Deuteronomy 12:9:4The Leningrad Codex of Deut 12:9 says “your (sing) God” (אֱלֹהֶיךָ) and “to you (sing)” (לָךְ) which BHK emends to “your (plur) God” (אֱלֹהֶיכֶם) and “to you (plur)” (לָכֶם) with the Septuagint (LXX), Samaritan Pentateuch (SP), and other ancient witnesses. BHS follows BHK while BHQ rejects the emendations as grammatical harmonization by the ancient versions. Weavers likewise sees the LXX translators (or the Vorlage) as pluralizing the pronouns to maintain consistency like the SP. See John William Wevers, Notes on the Greek Text of Deuteronomy (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995), 211. For kindred examples see apparatus of BHK/BHS/BHQ of Exod 23:13; Deut 9:7; 11:8; 13:6 (v. 6 in the Hebrew Bible is v. 5 in the English Bible); 14:3; etc.

You collectively shall not do as you collectively are doing here today, everyone doing what is right in their own eyes, because you collectively have not arrived at the resting place and inheritance that Yahweh

your personalyour collective God is giving toyou personallyyou collectively (as emended by BHK/BHS).You collectively shall not do as you collectively are doing here today, everyone doing what is right in their own eyes, because you collectively have not arrived at the resting place and inheritance that Yahweh your personal God is giving to you personally (as retained by BHQ).

These shifts in scholarly tendencies do not reflect a shift in tastes as much as a different view of the evidence. Ancient Hittite instructions as well as Mesopotamian and Aramaic treaties of the second and first millennia BCE include sudden shifts between second person singular and plural.5See Moshe Greenberg, “The Design and Themes of Ezekiel’s Program of Restoration,” Interpretation 38 (1984): 187 [181–208]; Kenneth A. Kitchen, “Ancient Orient, ‘Deuteronism,’ and the Old Testament,” in J. Barton Payne, ed., New Perspectives on the Old Testament (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1970), 4, 21, n. 23 [1–24]. This evidence suggests the shifts between second person singular and plural pronouns in Torah may not require source critical or text critical solutions. Many biblical scholars today work with the traditional received scriptural text (Masoretic Text) except when compelling evidence suggests otherwise.

In a previous generation no one was swifter to seek out source critical solutions to irregularities in Torah than Samuel Rolles Driver. Yet in the case of shifts from singular to plural second person pronouns and vice versa in Deuteronomy, even he saw the shifts as natural, not requiring source critical solutions. Driver rightly says: “The change . . . from the plural to the singular (or vice versa) is very frequent, sometimes taking place even within the limits of a single sentence.”66. S. R. Driver, Deuteronomy, International Critical Commentary (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906), 21.

Driver sees three categories. Israel could be addressed: (1) by the second personal plural; (2) as a whole collectively by second person singular; or (3) in the persons of its individual members by second person singular.7See ibid. It is easy to agree with Driver here, except one category might be added: (4) when Israel is being addressed as a whole in the singular, a shift to the plural may be a way to identify the individual citizens who together make up Israel.8Notice, e.g., the shift from second person singular as collective Israel in Deut 7:1–4a to second person plural in v. 4b—“then Yahweh’s anger will erupt against everyone of you” (בָּכֶם)—to refer to all of the individual citizens of collective Israel. Thus, in a context dominated by second person singular referring to Israel as a collective, a sudden shift to second person plural can be a way to emphasize the individuals that together comprise the collective. This means it is too simplistic to say singular = individual and plural = collective.

The present study will briefly survey a series of related laws concerning the socially disadvantaged appearing in several legal collections of Torah. These examples will serve as a basis for selected implications.

Examples of Shifts between the Second Person Singular and Plural in Torah

The following discussion of examples of legal instructions concerning social responsibility is restricted to shifts between singular/plural pronouns. A lot of other contextual concerns need to be set aside here. In these examples boldface type signifies second person whether the pronouns are built into the verbs, spelled out as stand-alone terms, or attached as pronominal suffixes. I have purposely over-translated second person pronouns for the sake of this study.

Notice the singular/plural shifts in the covenant collection’s prohibitions against mistreating the protected classes (Exod 21–23). The expression “residing foreigner” refers to landless outsiders who seek refuge in Israel. The first shift in 22:21 grounds personal responsibility within the collective identity of redemption. Collective redemption drives individual responsibility (cf. parallel version in 23:9):

You personally shall not mistreat or oppress a residing foreigner, because you collectively were residing foreigners in the land of Egypt. 22 You collectively shall not abuse any widow or orphan. 23 If you personally abuse them at all when they cry out to me I will certainly listen. 24 My anger shall blaze and I will kill you collectively with the sword, and your collective wives will become widows and your collective children orphans. (Exod 22:21–24)9Exodus 22:21–24 in the English Bible is vv. 20–23 in the Hebrew Bible. The translation “abuse them at all” (v. 23[22]) is based on the infinitive absolute which emphasizes the importance of the condition. See Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar, ed. Emil Kautzsch, trans. Arthur E. Cowley, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Claredon, 1910), §113o.

The shift from singular to plural in vv. 23–24 requires thought. Is the threat in v. 24 against the individual abusers of v. 23 as an aggregate collection of individuals? Maybe. But elsewhere in Leviticus 20:4–5 Yahweh threatens judgment not only against those who perform child sacrifices but also against anyone who knowingly does not prevent others from child sacrifice. Does v. 24 threaten exile against Israel if they do not intervene on behalf of the protected classes being abused among them? Such a reading of v. 24 fits the kind of covenantal rationale Amos uses to threaten exile against the northern kingdom of Israel (cf. Amos 7:17).

The legal standard for residing foreigners in Leviticus 19 likewise works back and forth between individual/collective identity and responsibility. By way of background, Exodus 3:22 thinks of residing foreigners sometimes living within the households of individual Israelites.10Exodus 3:22 uses the feminine singular participle form of the verb gvr (גור) to refer to a “female residing foreigner” with an equivalent function to the noun of the same root, namely, ger (גֵר). See “גור” DCH rev ed. 2:377b; “גור” HALOT 1:184. Notice how that kind of individual scenario serves as part of the basis or rationale for the prohibition against collectively mistreating them in v. 33:

When a residing foreigner resides with you personally in your collective land, you collectively shall not mistreat the residing foreigner.34 The residing foreigner residing among you collectively must be treated as the citizen among you collectively. You personally shall love the residing foreigner as yourself, because you collectively were residing foreigners in the land of Egypt. I am Yahweh your collective God. (Lev 19:33–34)

After establishing the standing of residing foreigners collectively within Israel collectively in v. 34a, the call upon individual Israelites to love the residing foreigner is again grounded in the collective identity of Israel as a redeemed people in v. 34b. Thus Leviticus 19:33–34 bases collective responsibility on personal realities and grounds individual responsibility upon collective identity.

But if the two individual-oriented elements of Leviticus 19:33–34 are connected, it raises a question. Does the responsibility to personally love residing foreigners as oneself relate only to those personally known because they live in one’s household? Deuteronomy represents this legal standard in a way that closes this potential loophole. The rare syntactical construction of “love the residing foreigner” in Leviticus 19:34 gets replaced with conventional Hebrew syntax in Deuteronomy’s version, making it nearly certain that the latter is the receptor context—later texts tend to disambiguate grammar and syntax.11See Schnittjer, OT Use of OT, 44, n.14. Notice how the later version of the law builds upon the earlier version:

You collectively shall love the residing foreigner, because you collectively were residing foreigners in the land of Egypt. (Deut 10:19)

The context of Deuteronomy 10 emphasizes that Yahweh protects the vulnerable classes and loves residing foreigners and provides for their needs (v. 18). If Israel is called upon to collectively love the residing foreigner, they imitate Yahweh and become instruments of Yahweh’s love by providing for the hardships faced by the outsider. The responsibilities of Israel collectively to love the residing foreigner does not get satisfied by individual citizens caring for individual residing foreigners that they know personally (Lev 19:33a, 34b). Israel collectively needs to act as Yahweh does toward residing foreigners by proactively helping them with necessities (Deut 10:18–19). For all of this it would be a mistake to think that Deuteronomy is skewed toward collective social responsibilities.

The torah collection of Deuteronomy 12–26 emphasizes the personal and individual implications of redemption as much as any legal collection in Torah. Notice the individual focus of parallel legal instructions in the torah collection.

You personally shall not pervert the justice due to a residing foreigner or orphan, and you personally shall not take a widow’s garment as security for a loan. 18 You personally shall remember that you as a singular collective were a slave in Egypt and Yahweh your personal God redeemed you as a singular collective from there. Therefore, I am commanding you personally to do this thing. (Deut 24:17–18)

All seven second person pronouns in vv. 17–18 are singular. All seven could be translated “you personally/your personal.” But the Egyptian slavery and divine redemption in v. 18 are collective not merely personal. For present purposes I have chosen to translate only these two as “you as a collective singular.” The same could arguably be done to four of the five other pronouns based on the identity of you singular in Egyptian slavery and redemption. But the particularity of the prohibition against taking as collateral a widow’s garment (v. 17) suggests that these are personal responsibilities even if they are grounded in Israel’s collective identity.

Implications

This study was not born out of any of today’s social or political concerns. It was born out of reading Torah’s laws in Hebrew.

The case studies on standards concerning the protected classes in the legal collections of Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy all point in the same direction relative to the interchange and function of second person singular and plural pronouns. The legal standards freely move between second person individual and/or collective identity and their associated individual and/or collective responsibilities. As Israel, so its citizens, and vice versa.

The legal standards do not seem to be overly self-conscious in the shifts from singular to plural and back. It is as though the overlap of collective and personal identity are entirely natural.

Are moderns radical individualists? No one doubts this. But the solution is not to eradicate personal responsibility or even to replace personal identity with collective identity. The legal standards of Torah emphasize the personal identities and the personal responsibilities of the redeemed assembly without flinching.

The generic “you” of the English Bible seems to have deafened the ears of moderns already predisposed to self-autonomy. The legal standards of the Hebrew Bible promote a different view of the identity and responsibilities of God’s people. Torah does not do away with the individual in favor of the collective.

An either/or-mindset of individual versus collective identity and responsibility is not the solution. A categorical choice between the individual and the collective seems fully at odds with the both/and-legal-standards of Torah. Identity and responsibility of the redeemed in Torah encompass thou and ye, thee and you.12Thank you to Keith Plummer for feedback on an earlier draft of this essay.

Copyright © 2022

Gary Edward Schnittjer

End Notes

1. See Gary Edward Schnittjer, Old Testament Use of Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, 2021), 834–39; cf. 279–81; 323–24; Gary Edward Schnittjer, “Individual versus Collective Retribution on the Chronicler’s Ideology of Exile,” Journal of Biblical and Theological Studies 4.1 (2019): 113–32. For other interaction with individual and collective perspectives in Scripture, see Gary Edward Schnittjer, Torah Story, 2nd edition (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, forthcoming), chap 24 ad loc; Gary Edward Schnittjer, “The Bad Ending of Ezra-Nehemiah,” Bibliotheca Sacra 173 (2016): 49–55 [32–56].

2. Table of pronouns from D. Fenning, The Royal English Dictionary; or, a Treasury of the English Language, 4th ed. (London: Printed for L. Hawes and Co., 1771), 20 [public domain].

3. Biblia Hebraica, ed. by R. Kittel, 3rd ed. (Stuttgart: Bibelanstalt, 1937), hereafter cited as BHK; Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, ed. by Karl Ellinger, Wilhelm Rudolph, et al., 5th ed. (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1997), hereafter cited as BHS; Innocent Himbaza, ed., Leviticus: Biblia Hebraica Quinta (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2020), hereafter cited as BHQ; Carmel McCarthy, ed., Deuteronomy: Biblia Hebraica Quinta (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2007), hereafter cited as BHQ. All translations of Biblia Hebraica are mine unless stated otherwise. All emphases added to translations are mine.

4. The Leningrad Codex of Deut 12:9 says “your (sing) God” (אֱלֹהֶיךָ) and “to you (sing)” (לָךְ) which BHK emends to “your (plur) God” (אֱלֹהֶיכֶם) and “to you (plur)” (לָכֶם) with the Septuagint (LXX), Samaritan Pentateuch (SP), and other ancient witnesses. BHS follows BHK while BHQ rejects the emendations as grammatical harmonization by the ancient versions. Weavers likewise sees the LXX translators (or the Vorlage) as pluralizing the pronouns to maintain consistency like the SP. See John William Wevers, Notes on the Greek Text of Deuteronomy (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995), 211. For kindred examples see apparatus of BHK/BHS/BHQ of Exod 23:13; Deut 9:7; 11:8; 13:6 (v. 6 in the Hebrew Bible is v. 5 in the English Bible); 14:3; etc.

5. See Moshe Greenberg, “The Design and Themes of Ezekiel’s Program of Restoration,” Interpretation 38 (1984): 187 [181–208]; Kenneth A. Kitchen, “Ancient Orient, ‘Deuteronism,’ and the Old Testament,” in J. Barton Payne, ed., New Perspectives on the Old Testament (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1970), 4, 21, n. 23 [1–24].

6. S. R. Driver, Deuteronomy, International Critical Commentary (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906), 21.

7. See ibid.

8. Notice, e.g., the shift from second person singular as collective Israel in Deut 7:1–4a to second person plural in v. 4b—“then Yahweh’s anger will erupt against everyone of you” (בָּכֶם)—to refer to all of the individual citizens of collective Israel. Thus, in a context dominated by second person singular referring to Israel as a collective, a sudden shift to second person plural can be a way to emphasize the individuals that together comprise the collective. This means it is too simplistic to say singular = individual and plural = collective.

9. Exodus 22:21–24 in the English Bible is vv. 20–23 in the Hebrew Bible. The translation “abuse them at all” (v. 23[22]) is based on the infinitive absolute which emphasizes the importance of the condition. See Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar, ed. Emil Kautzsch, trans. Arthur E. Cowley, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Claredon, 1910), §113o.

10. Exodus 3:22 uses the feminine singular participle form of the verb gvr (גור) to refer to a “female residing foreigner” with an equivalent function to the noun of the same root, namely, ger (גֵר). See “גור” DCH rev ed. 2:377b; “גור” HALOT 1:184. Thank you to Jeremiah Unterman for drawing my attention to the participle in Exod 3:22.

11. See Schnittjer, OT Use of OT, 44, n.14.

12. Thank you to Keith Plummer for feedback on an earlier draft of this essay.

Subscribe now to receive periodic updates from the CHT.

Image created by Rubner Durais